Politicon.co

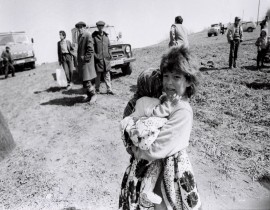

Woman of Tehran, woman of South Azerbaijan: the impact of environment and society on gender roles

Initially, this article was supposed to compare the situations of Western and Middle Eastern women. However, while researching, I came across some interesting, dubious statistics. If you search “the average age for marriage in Iran” on Google, you will get a result from a study on Wikipedia indicating an average age of 29.5 for men and 25 for women. It also cites a study in which 80% of female students also have premarital sex. My curiosity took the better of me, and the deeper I dug, the more my article’s topic changed. I had to know, how accurate are these results?

Do they really represent the women of Iran? Are women really in control of their own lives and relations? As a woman who has spent much of her life in Iran, living in both Tehran and Tabriz, this was news to me. Of course, with a bit more research, the second study turned out to be inaccurate. I will debunk the numbers and discuss the problems with the numbers later in this article. I questioned the statistics because I intuitively sensed that the numbers were wrong based on my experience in the real world. At the same time, I became curious about one question: what factors fundamentally shaped my experience specifically and more generally women’s status in society, from the perspective of behavioural biology? I decided that my article would answer this question, specifically considering the environment’s effects on culture and society, comparing women in Tehran to women in South Azerbaijan.

Understanding women’s status through behavioural biology

To understand the varied status of women in different parts of Iran, let us consider a few of the main causes that affect the status of women in society.

1. Types of farming present in the society

Historically, a society’s use of the plough or the hoe for agriculture has had surprising ramifications for the position of women. A plough is a heavy (between 500-1500 lbs) farm tool made of iron or wood that is dragged on the soil to loosen or turn the soil for seed plantation. The device was historically handled either by one or more men or by oxen.

The hoe on the other hand is a small, handheld device that would be used for the same purpose as the plough, but in smaller areas at a time.

Depending on which item was used on the soil, the position of women in society changed. Men were better suited for handing the plough or the oxen due to their size and physical strength. Women, in contrast, also needed to attend to their children and had to be able to stop their fieldwork when their child was in distress to help them. Using the hoe gave women the advantage of being able to work in the field while also attending to their children. As a result, societies that predominantly used the plough split agricultural work, such that women would focus on domestic tasks while men worked in the fields. This gradually domesticized women, who would be totally occupied at home, while the society outside developed without them. Practical necessity created entrenched norms that left no space for women outside of the home.

Returning to regional differences, Azerbaijan is unusual among its neighbours, as it did not use the plough as the dominant method of agriculture (this would mean that it was not the main method, rather than not used at all). This suggests that historically agricultural work and society did not develop without space for women. However, that the plough was not used does not automatically mean that the hoe was used instead. We have to consider that humans can harvest food by means other than agriculture, which leads us to the next point:

2. Pastoralism

Pastoralism plays an important role in women’s position in society, although this is primarily true in societies that largely survive off their herds and that cannot successfully obtain resources in other ways.

Herding culture leads to strong territorial instincts due to the need to protect grazing lands, water sources, and livestock from competitors or raiders. Unlike sedentary agricultural societies with fixed land boundaries, pastoralist groups frequently move within a defined range, leading to conflicts over seasonal grazing rights. Such conflicts foster feelings of group identity and cause men to develop more aggressive, hierarchal, and territorial behavior to protect their herds and territorial claims. The idea is that if you are weak or soft and let the other group take your gazing land, your herd will starve, and then so will you. Or, “If they take your camel today and you do nothing, tomorrow they will take the rest of your herd, plus your wives and daughters!” Consequently, pastoralist societies create aggressive males, obedient and domestic women, and a strong hierarchy amongst men, women, and groups. Looking at the history of Azerbaijan, we see a mixture of both agricultural societies (especially in the lowlands) and pastoralists (especially in the highlands). This mix would have reduced the effects of pure pastoralism and have given multiple resources for survival for Azerbaijanis.

This leads us to the next important factor:

3. Water scarcity

Water is crucial for all life. Without water, crops will not grow and herds will die of thirst (as will humans). Lack of water resources will cause intense stress on the population, high levels of territorialism, and increased aggression. Women are especially vulnerable in these situations. Stats for child marriages, forced migrations, trading of women, domestic violence, and rape increase in the population living in water scarcity. Just like in herding societies, men are better fit for defending water territories. However, women are typically primarily responsible for fetching water, which will cause them to stay away from income-gathering activities and education. Depending on the water source’s location, women would also face various dangers journeying to and from the water source.

4. Religiosity

Big religions work by increasing the chances of “cultural selection”: religious cultures thrive and spread by having followers who are more devout and simply by increasing the number of followers. Throughout human existence, Abrahamic religions have been one of the most successful at this. However, in societies with increased rates of religiosity, the role of women diminishes because to win the cultural selection game, a culture will need to both invite new followers and grow new followers by reproduction. In most religions, especially the Abrahamic ones, having multiple children is encouraged. To make this feasible, you will need to have women in more obedient, domestic, and childbearing roles, thus excluding and discouraging (if not punishing) them from taking any other roles in society.

5. Industrialization

Industry is a fifth important factor that affects women’s place in society. Industrialized societies have different requirements for recruits than non-industrialized ones. For example, heavy labor is done by machinery, which increases productive output and makes production faster and more efficient. With the expansion of industrial production, the requirement for tending to machines and overseeing this production increases, so more workers are needed and education is required for these workers. Eventually, the demand for workers expands into recruiting women as well, thus pushing women towards studying and having a career. This combined with the urbanization of the society creates a very different society than the other ones. Women are encouraged to be independent from domesticity and family networks, and have access to education, healthcare, birth control, and justice to ensure they can contribute to industry. Most sudden surges in the popularity and success of feminist movements followed periods when women’s contribution to society was increasingly required, such as with industrialization, times of war when men were off fighting on the battlefield, and regimes such as communist ones that required the entire society to contribute.

_____

Let us now consider how the five factors from behavioural biology that I discussed above impact women’s conditions in South Azerbaijan as opposed to the women of Tehran.

Though I previously talked about the impact on women of using a plough versus a hoe for agriculture, we should also consider the differential impact of modern agriculture on women. In my opinion, while the hard labour required in using a plough ultimately benefits men’s status as the main agricultural producers, modern agriculture’s reduced demands for hard physical labour can be beneficial to women. In the case of Iran, farmers in central and Persian parts of Iran, (such as Isfahan and Yazd) have modern tractors, drip irrigation systems, and state-funded fertilizers and pesticides. They receive subsidies for high-tech greenhouses, automated irrigation, and genetically improved seeds. Central region farmers get low-interest loans for purchasing modern farming equipment making farming more profitable and efficient in central Iran.

On the other hand, Azerbaijani farmers struggle to get bank loans and are excluded from major government agricultural programs. Unlike their counterparts in Tehran and Isfahan, Azerbaijani farmers lack access to subsidized fertilizers, pesticides, and improved seeds. They must continue with older agricultural methods, similar to the plough, which require more labour, an older tractor, manual watering (usually through wasteful canals), and manual actions against pests due to lack of pesticides. The government also has not invested in sustainable farming methods in Azerbaijan, further worsening agricultural output. The outcome of this varied support for agricultural modernization should, in my opinion, be similar to the use of a plough versus a hoe. Outdated farming methods and machinery require more labour for which women are not fit, resulting in them taking domestic roles.

Additionally, stats about water scarcity in Azerbaijani provinces are increasingly concerning. The Iranian state actively drains or redirects water from Azerbaijani provinces into the central provinces for domestic and agricultural uses, but also for making faux lakes. Lake Chitgar of Tehran is an example of a large faux lake, while Lake Urmia in Azerbaijan has dried up, with disastrous consequences for the region. Azerbaijan’s rivers and underground water are heavily extracted and diverted to central regions, leaving local farmers with dry fields and low crop yields. Central Iranian provinces, on the other hand, receive government-funded irrigation projects and water pipelines from Azerbaijani regions to sustain their agriculture. The Chaharmahal-Bakhtiari water transfer project diverts water from Azerbaijani regions to central Iranian farmlands.

Water scarcity leads to decreased agricultural yields, and since agriculture is a main economic activity in South Azerbaijan, families become economically strained, pushing them into deeper poverty. Families facing economic hardship often resort to marrying off young girls prematurely. Child marriage thus becomes a coping mechanism to reduce economic burdens, with daughters being increasingly seen as a liability or otherwise a crop ready to be sold once ready. As a result, the girls will be excluded from education or respect. However, these early marriages are not only meant to benefit the family financially, but are also seen as means to a better life for the girls, such as by marrying them off to a wealthier man. The proof for the effects of water scarcity has been shown in the study: in child marriages (girls under 15) between 2007 and 2021:South Azerbaijani Provinces consistently recorded higher proportions of child marriages compared to Iran's national average.

For example, in Ardabil (2021), child marriages accounted for 11% of total marriages, nearly double the national average (5.7%). Zanjan (13.69%) and East Azerbaijan (11.34%) also significantly exceeded national averages. Similarly, In East Azerbaijan, there was a 42% increase in child marriages between 2017 and 2019. A horrifying statistic shows that over 55% of marriages in Sar'ein county of Ardabil involved girls under 18 in 2020. These figures are considerably higher than the national average, where approximately 21% of women marry before 18, and 5% before 15. (These stats are in extreme contrast with the study mentioned at the beginning of this article, which may represent only women in privileged central parts of Iran and in no way an accurate representation of all women in Iran.)

Water scarcity and the use of outdated agricultural methods have also caused soil degradation, especially given the expected salt storms as a result of the drying of Lake Urmia. While specific quantitative data on the recent increase in individuals shifting to pastoralism in Southern Azerbaijan is limited, the environmental pressures suggest a logical shift towards such practices as alternative livelihoods which leads to the further demise of women. In my quick data search I noticed between the 2014 agricultural census and the 2023 livestock survey that although South Azerbaijan remains fairly stable in the number of sheep, number of goats in East Azerbaijan jumped by 35 %, West Azerbaijan 46%. Goats are a "Hardier livestock", which refers to animals that are more resilient and adaptable to tough environmental conditions. suggesting a drought‑driven tilt toward hardier livestock, Still, the available data do not yet prove a wholesale shift to pastoralism; finer‑grained studies will be needed to see whether household labour and income are truly pivoting toward herding.

The industry is also massively different between Azerbaijan and central Persian regions. Tehran, Isfahan, and Mashhad have large-scale automobile, petrochemical, and steel industries, which receive state investments and subsidies. Tehran has over 40% of Iran’s industrial production capacity, with numerous high-tech zones, manufacturing plants, and research centers. The central government supports these areas with preferential energy and water supply, tax incentives, and export facilities. Central regions also receive priority access to bank loans, government grants, and credit lines for industrial projects. Azerbaijani provinces, on the other hand, lack major industries, forcing people to rely on low-income agriculture and traditional trades. There are no large government-funded manufacturing plants in East or West Azerbaijan, despite the provinces' economic potential. Limited infrastructure investment means industrial zones in Azerbaijani cities remain underdeveloped or non-functional.

The economic diversification and industrial infrastructure of the central provinces provide robust employment alternatives beyond agriculture, creating economic resilience and reducing vulnerability to environmental fluctuations. The contrast is seen in Azerbaijani provinces, which have also been described as internal resource colonies, as the Iranian state extracts their resources for central Persian regions’ benefit, without developing local industry. These provinces depend on agriculture and herding for survival, leaving them extremely vulnerable to environmental crisis. Should any Azerbaijanis wish to invest in industry, they will do so by moving their factories and hubs to the central parts to receive government benefits and subsidies.

Finally, religiosity correlates with trust in government: the higher the trust in government justice, the lower the rates of religiosity. Conforming to this pattern, Azerbaijan is known as one of the more conservative and religious parts of Iran, while a large number of people in central parts of Iran consider themselves nonreligious or spiritual. This not only showcases the Azerbaijani population’s lesser trust in state justice, but also the likely greater marginalization of Azerbaijani women that would accompany increased religiosity.

Besides the stark contrast in the way in which the women of the same country and same law live, let us not forget that an Azerbaijani woman, similar to her male counterparts,, also has to pass through the barrier of forced assimilation. This leaves her with even more challenges to face in her life than those faced by the woman of Tehran.

As long as these provinces remain under internal colonization, the women’s situation and status will deteriorate. Although I did not address this above, social media and the internet also impact a society’s beliefs and culture, possibly improving general notions about women’s status. However, let us not forget that to access social media, you will need the funds to afford the internet and a phone or computer, which is more likely to be true for those living in cities. Poverty rates in Azerbaijan have more than doubled in the past decade. Poverty rates in West Azerbaijan, for example, have more than tripled, from 13.6% to 44%. (Women’s employment rate in this? 15%.) Consequently, social media will not be accessible for marginalized families or families living in villages or small towns.

For this downfall to change, serious measures need to be taken. Farmers need to be supported and given modern agricultural equipment, industry needs to be supported and invested in, and natural resources managed properly. All these things will not be possible as long as South Azerbaijan remains a colony.

Citations:

- Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Marriage in Iran. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 6, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marriage_in_Iran

- Alesina, A., Giuliano, P., & Nunn, N. (2013). On the origins of gender roles: Women and the plough. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2), 469‑530.

- Boserup, E. (1970). Woman’s Role in Economic Development. St. Martin’s Press.

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2017). Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. Penguin Press.

- Ember, C. R., Skoggard, I., & Jones, S. (2014). War, socialization, and intergroup conflict in pastoral societies. Human Nature, 25(3), 393‑409.

- Keshavarz, A. (2025, April 20). The countdown to Iran’s day zero: A crisis of water, not war. Untold Magazine.

- AHRAZ; Water Crisis in Iran episode 9. ahraz.org

- UNICEF MENA Regional Office. (2021). Child marriage in the Middle East and North Africa (Fact sheet).

- UNICEF. (2022). Towards ending child marriage: Global progress and trends (Statistical brief).

- Norenzayan, A. (2013). Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict. Princeton University Press.

- Association for the Rights of Cultural Diversity & Human Rights (ARCDH). (2024, June 14). ARCDH warns the UN Human Rights Council about the dire situation of Azerbaijanis in Iran. https://www.arcdh.eu/arcdh-warns-the-un-human-rights-council-about-the-dire-situation-of-azerbaijanis-in-iran/

![]()

- TAGS :

jpg-1599133320.jpg)